By Howard Gold, PhD student, English

Department, Old Dominion University.

re-posted September 22, 2016

|

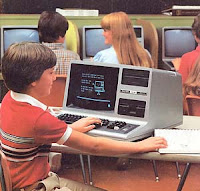

| Radio Shack TRS "Trash" 80 Model III in school |

Writers of every ilk are

indebted to mathematicians and engineers who built early information-storage

and retrieval systems during the mid-twentieth century. Without those, the age

of personal computing and word processing could not have exploded in the 1980s.

The pervasive use and ease of digital documentation quickly replaced

traditional typewriters, expanding storytelling, documented teachers’ notes, encouraging

a global sharing of academic findings and more, from the highest levels of

academia and government to neighborhood schools and kitchen tables. This occurred

during a quick evolution of word-processor-centric computers available at

retail stores, such as Radio Shack’s popular TRS-80, the WANG VS series,

Commodore’s 64, leading up to the early IBM Personal Computer (“PC”) and

Apple’s first MAC, all using software from WordStar to WordPerfect to Microsoft

Word. “These instances are also contextualized

as signifiers of the culture’s general adoption of personal computers in

writing and the office environ” (Lambertson).

Of course, we know this now. But how

did we get here? When did digital documentation begin, and how did it become a

mainstay of our culture? This essay is a brief statement of key issues for

consideration.

Technically speaking…

From a technical

view, we start at 1940s Princeton with John von Neumann's first data-storing computer (Atomic Archive). That led to his work (with fellow mathematicians and

engineers) on the USS Nautilus, launched on January 21, 1954, which did not set

sail September 30, 1954 (Submarine Force Museum).

Anecdotal reports contend that the delay was caused by–among other reasons–documentation

and a simple matter of physics. The documentation for everything from repairing

stoves to launching nuclear missiles was reportedly heavier and of more volume

than the ship itself. All the manuals needed to be digitized and capable of

storing “programming information” with easy-to-read “data” as text. Previously,

only numerical data for computation was stored, making this copying of files to

microfiche or computer tape for storage and retrieval on board a military

vessel ground-breaking.

|

| USS Nautilus at sea |

Philosophically speaking…

In “Orality and Literacy" (1982), Walter J. Ong

states that writing is a technology, but “Technologies are artificial—paradox

again—artificiality is natural to human beings. Technology, [properly

interiorized, does not degrade human life but on the contrary enhances it” (Ong). In the same text, he points out that

consciousness of ideas cannot be fully realized without writing. The

interaction of speech, “orality”, is something that we are born with, while

writing is a learned activity. Writing is an extension of orality, and is

therefore “consciousness-raising.” Over thirty years ago, Ong stated that

electronically or digitally produced text could replace books or newspapers,

and foresaw a growth of what we now call eBooks and audio texts (Ong).

Modernist view…

So, where did we writers and students get the big idea

that we can adopt technology created by mathematicians and the Department of Defense

and for our tasks? Before migrating to

digitized text, writers’ thoughts and even the thinking process—the order of prioritizing

thoughts, documenting

them, creating new ideas, purging unworkable ones—was already

underway before 1900 when Nietzsche typed the phrase, “Our writing

instruments are also working on our thoughts (Kirschenbaum). Anne Rice, who came of age in the computer era reveals that,

despite writing in different genres, their thinking changed by using computers

to write. Anne Rice admits, “Once you really get used to a computer and you get

used to entering the information from that keyboard, things happen in your

mind, I mean, you change as a writer. You’re able to do things that maybe you

never would have thought of doing before.”

|

| Anne Rice books on Amazon |

We creators of digital documentation, from poets to tech

writers, are faced with two roles: author and reader. As authors, it is easy to

let the words come out of our brains, through our fingers, across the keyboard,

and onto the screen in various levels of awareness. But care must be taken, as

each digital writer is also a member of their own audience. The writer can

often see the working version of a draft in the same format as the audience, removing

the middle-steps of production and publication. Jerome

McGann’s contends that perceiving text today requires “emulate[ing] the humanists of the fifteenth

century who were confronted with a similar upheaval of their materials, means,

and modes of Knowledge production” (qtd. by O'Sullivan).

This new digital literacy

requires new skills for authors and readers alike, bringing new phrases of like

transliteracy, metaliteracy and multimodal literacy

to the forefront (Stordy).

References

Jabr, Ferris. "The Reading Brain

in the Digital Age: The Science of Paper versus Screens." Scientific

American 11 Apr 2013. 18 Sep 2016.

<http://www.scientificamerican.com/article/reading-paper-screens/>.

Kirschenbaum, Matthew.

"Technology changes how authors write, but the big impact isn’t on their

style." 26 Jul 2016. The Conversation. 19 Sep 2016. https://theconversation.com/technology-changes-how-authors-write-but-the-big-impact-isnt-on-their-style-61955.

Lambertson, Jessa A. "Track

Changes: A Literary History of Word Processing." Library Journal

(2016): 91. 18 Sep 2016.

National Science Digital Library.

"John von Neumann (1903 - 1957)." 2015. Atomic Archive. AJ

Software & Multimedia, National Science Foundation Grant 0434253 . 21 Sep

2016. <http://www.atomicarchive.com/Bios/vonNeumann.shtml>.

Ong, Walter J. Orality and Literacy.

New York: Routledge, 1982, 2002. 18 Sep 2016.

O'Sullivan, James. "The New

Apparatus of Influence: Material Modernism in the Digital Age." International

Journal of Humanities and Arts Computing 8.2 (2014): 226-238. 20 Sep 2016. www.euppublishing.com/ijhac.

Stordy, Peter Howard. "Taxonomy

Of Literacies." Journal of Documentation 71.3 (2015): 456-476. Applied

Science & Technology Source. Web. 22 Sept. 2016.

Submarine Force Museum. Submarine

Force Museum, Home of the Historic Ship NAUTILUS. 2013. 18 Sep 2016.

<http://www.submarinemuseum.org/nautilus/index.shtml>.

This essay may be revised and replaced.

ReplyDeleteIn your last paragraph, you touch upon the concept of being audience as writer, the idea of the draft being in the same format of the publication. In turn, that's quite powerful, I think, because it invites a recursive editing process that authors such as Nancy Sommers suggest distinguish student writers from mature writers. One of the things Sommers highlights is that experienced writers view their material and experience dissonance between what they have said and what they meant to say, thus allowing their own writing to prompt a discovery (knowledge building) process (387). This seems to tie into Ong's extended orality, as you've mentioned it in your post. On top of that, widespread adoption of technology has made it easy for writers to enjoy that experience, because it's no longer necessary to have work published--one can see it on the screen, as you've said, in the same format as the reader will see it.

ReplyDeleteYour new modes of knowledge production seem like they're at play here. And like they're pretty awesome!

Sommers, Nancy. "Revision Strategies of Student Writers and Experienced Adult Writers." College Composition and Communication, vol. 31, no. 4, 1980, pp. 378-388.

Heather, Thank you that observation, especially relative to "allowing their own writing to prompt a discovery (knowledge building) process." That was what I as going for. The revised paper opens a discussion about the academic side of this argument: why technical communication should be taught as part of the English Studies curriculum. I really appreciate your feedback!

Delete