Paper 1, revised: Summary: a short history of Technical Communications as English Studies (ODU 810)

|

| NYC Middle Schoolers online |

Selfe and Hawisher consider how Technical

Communicators “acquired” electronic literacy, what influenced that gain, and

identify similarities to help “Technical Communicators instructors, program

directors, and workplace supervisors” effectively teach electronic literacy The inclusion of Technical Communications in the English Studies curriculum

leads to a commitment to digital rhetoric in the college curriculum. Technical

Communications is closely related to Digital Rhetoric. Both skills require digital literacy, which include the

“practices of reading, writing, and exchanging information online, with the

values associated with such practices—social, cultural, political, [and]

educational”[1]. For

these reasons, the study and teaching of Technical Communications and Digital

Rhetoric should remain in the English Studies department, not in the growing

number of more technically-oriented Communications departments.

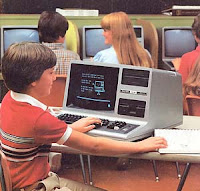

The computer explosion took place

from 1978 through 1993, which is no secret. In 1984 Gilbert Storms noted that technical communications

courses be added to the curriculum, showing “how they are used in communication,

particularly word processing, information storage and retrieval, and

information management”[2].

Jessica Lambertson recently praised

technical communication in the digital age for expanding storytelling, simplifying

the documentation of teachers’ notes, encouraging a global sharing of academic

findings from the highest levels of academia and government to neighborhood

schools and kitchen tables. “These

instances are also contextualized as signifiers of the culture’s general

adoption of personal computers in writing and the office environ”[3].

Of course, we know

this. But this paper covers these questions:

- When did the subdiscipline of Technical Communication emerge?

- What universities did it emerge from?

- What were the exigencies for its emergence?

- What was its relationship to the university system as a whole?

Technical Communication Subdiscipline Emerges

As early as 1980, two

years into the personal computer revolution, Jacques G. Richardson of UNESCO announced the global value of

the interdisciplinary responsibility of Technical

|

| Walter J. Ong |

The Golden Age

|

| President Clintion |

The discipline of Technical

Communications in the university’s

English Studies department came out of President Bill Clinton’s 1993 Technology

Literacy Challenge validated teaching technology literacy to K-12 students[7].

Digitally literate high school grads were joining the entry-level workforce just

when PCs were cheap and ubiquitous in all businesses. That socio-economic

reality required adding Technical Communications to the college curriculum[8].

Digital rhetoric takes us a step further

into a world where we structure “content for a future that’s unfixed, fluid and

ever changing. Miles Kimbal, of Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, contends that

after thousands of years of oratory and rhetoric, the early 21st

century is “the Golden Age of technical communication. [… and we] should spread

it as a set of skills valuable for everyone to learn”[9]

Today’s Golden Age of Technical

Communication will lead to new level of digital rhetoric, expanded on by Lee-Ann Kastman Breuch, University of

Minnesota, when she explained that “issues of technological literacy related to

performance, contextual factors, and linguistic activities […] provide […] a

mechanism to identify and analyze a range of perspectives associated with

technology and communication”[10].

This pedagogical philosophy will support the view that the study and teaching

of Technical Communication as it evolves into Digital Rhetoric should remain in

the English Studies department.

Bibliography

Fromm, Harold. "The rhetoric and politics of

environmentalism." College English.. 59,

no. 8 (Dec 1997): 946-950.

Kastman Breuch, Lee-Ann. "Thinking critically

about technological literacy: Developing a framework to guide computer

pedagogy in technical communication." Technical Communication

Quarterly 11, no. 3 (2002): 267.

Kimball, Miles A. "The Golden Age of Technical

Communication." Journal of Technical Writing and Communication,

Apr 2016: 1-29.

Kirschenbaum, Matthew G. Track Chaanges.

Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2016.

Lambertson, Jessica A. "Track Changes: A Literary

History of Word Processing." Library Journal, 2016: 91.

Ong, Walter J. Orality and Literacy. New

York: Routledge, 1982, 2002.

Regents of the University of Minnesota. "Who

Was Charles Babbage?" The Charles Babbage Institute. 2015.

http://www.cbi.umn.edu/about/babbage.html (accessed Sep 24, 2016).

Richardson, Jacques G. "Science and Technology

as Integral Parts of Our Culture: Interdisciplinary Responsibilities of the

Scientific Communicator." Journal of Technical Writing and

Communication, April 1980: 141-147.

Saint Louis University. "The Ong Center

Home." slu.edu. 2016. http://www.slu.edu/the-ong-center (accessed

Sep 23, 2016).

Selfe, Cynthis L., and Hawisher, Gail E. "A

Historical Look at Electrroinic Literacy." Journal of Business and

Technical Communication, July 2002: 231-276.